Researchers have deciphered an ancient Egyptian handbook, revealing a series of invocations and spells.

Among other things, the “Handbook of Ritual Power,” as researchers call the book, tells readers how to cast love spells, exorcise evil spirits and treat “black jaundice,” a bacterial infection that is still around today and can be fatal.

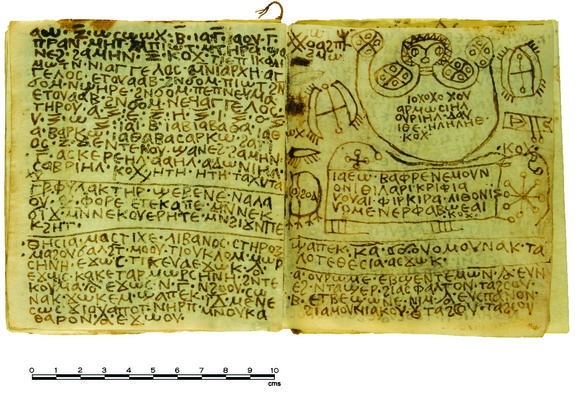

The book is about 1,300 years old, and is written in Coptic, an Egyptian language. It is made of bound pages of parchment — a type of book that researchers call a codex.

“It is a complete 20-page parchment codex, containing the handbook of a ritual practitioner,” write Malcolm Choat and Iain Gardner, who are professors in Australia at Macquarie University and the University of Sydney, respectively, in their book, “A Coptic Handbook of Ritual Power” (Brepols, 2014).

The ancient book “starts with a lengthy series of invocations that culminate with drawings and words of power,” they write. “These are followed by a number of prescriptions or spells to cure possession by spirits and various ailments, or to bring success in love and business.”

For instance, to subjugate someone, the codex says you have to say a magical formula over two nails, and then “drive them into his doorpost, one on the right side (and) one on the left.”

The Sethians

Researchers believe that the codex may date to the 7th or 8th century. During this time, many Egyptians were Christian and the codex contains a number of invocations referencing Jesus.

However, some of the invocations seem more associated with a group that is sometimes called “Sethians.” This group flourished in Egypt during the early centuries of Christianity and held Seth, the third son of Adam and Eve, in high regard. One invocation in the newly deciphered codex calls “Seth, Seth, the living Christ.” [The Holy Land: 7 Amazing Archaeological Finds]

The opening of the codex refers to a divine figure named “Baktiotha” whose identity is a mystery, researchers say. The lines read, “I give thanks to you and I call upon you, the Baktiotha: The great one, who is very trustworthy; the one who is lord over the forty and the nine kinds of serpents,” according to the translation.

“The Baktiotha is an ambivalent figure. He is a great power and a ruler of forces in the material realm,” Choat and Gardner said at a conference, before their book on the codex was published.

Historical records indicate that church leaders regarded the Sethians as heretics and by the 7th century, the Sethians were either extinct or dying out.

This codex, with its mix of Sethian and Orthodox Christian invocations, may in fact be a transitional document, written before all Sethian invocations were purged from magical texts, the researchers said. They noted that there are other texts that are similar to the newly deciphered codex, but which contain more Orthodox Christian and fewer Sethian features.

The researchers believe that the invocations were originally separate from 27 of the spells in the codex, but later, the invocations and these spells were combined, to form a “single instrument of ritual power,” Choat told Live Science in an email.

Who would have used it?

The identity of the person who used this codex is a mystery. The user of the codex would not necessarily have been a priest or monk.

“It is my sense that there were ritual practitioners outside the ranks of the clergy and monks, but exactly who they were is shielded from us by the fact that people didn’t really want to be labeled as a “magician,'” Choat said.

Some of the language used in the codex suggests that it was written with a male user in mind, however, that “wouldn’t have stopped a female ritual practitioner from using the text, of course,” he said.

Origin

The origin of the codex is also a mystery. Macquarie University acquired it in late 1981 from Michael Fackelmann, an antiquities dealer based in Vienna. In “the 70s and early 80s, Macquarie University (like many collections around the world) purchased papyri from Michael Fackelmann,” Choat said in the email.

But where Fackelmann got the codex from is unknown. The style of writing suggests that the codex originally came from Upper Egypt.

“The dialect suggests an origin in Upper Egypt, perhaps in the vicinity of Ashmunein/Hermopolis,” which was an ancient city, Choat and Gardner write in their book.

The codex is now housed in the Museum of Ancient Cultures at Macquarie University in Sydney.